On June 2, the recipients of the 2021 Joan Shaw Herman Award for Distinguished Service spoke at a virtual gathering of Concord Academy alumnae/i and other community members. Both Leslie Davidson ’66 and Ingrid Walker-Descartes ’91 were honored for their contributions to child protection, health, and advocacy.

This distinction is the only award given in the Concord Academy community. Befitting a school that eschews academic prizes or honors in favor of cultivating a collaborative, creative, intellectually driven, and mutually supportive environment, the Joan Shaw Herman Award is bestowed annually on a graduate in recognition of service to others.

It was the first time two alumnae/i have received the award in the same year. Working in related fields, both of these physicians have focused their life’s work on helping children who are among the most disadvantaged and vulnerable. Both have recognized the importance of working across sectors and have embraced opportunities to broaden their fields of expertise to better care for the individuals and communities they serve.

“Their work addressing pediatric trauma and children’s mental health, disability, and welfare is difficult, emotional, and often inconspicuous,” said Kate Rea Schmitt ’62, P’88, chair of the Joan Shaw Herman Award Selection Committee. “Leslie and Ingrid are children’s champions.”

Leslie Davidson ’66

A mother arrives at the hospital concerned about her 5-year-old daughter, who has a high fever and a severe sore throat. When an attending physician notices that the child’s chart includes no information about vaccination, she suspects diphtheria, though the disease has largely been eradicated in the United States. After the cultures come back positive, the child’s sister is also admitted. A third sibling, partially immunized, becomes ill, though not gravely. The fourth has had the full series of three shots and doesn’t become sick. Despite the intensive care they are given, the unvaccinated children die, and the mother loses a pregnancy as well.

This was how the first pediatric admission Davidson encountered as a medical student unfolded. “The family was destroyed because the system failed to get them a vaccine,” she said in her Joan Shaw Herman Award virtual presentation. The experience changed the course of her career. She knew she had to approach health from more than a medical perspective alone.

Davidson said she knew she wanted “one foot in the academy and one foot in the community,” to integrate clinical pediatrics and public health. After earning a master’s in epidemiology and completing a post-doctorate in child psychiatry, she accepted a job leading the Central Harlem School Health Program, where she oversaw 12 schools—and the health of 11,000 children—in Harlem, N.Y. “It was a place where public health could make a huge difference,” she said.

Partnering with the head of pediatric surgery, Davidson launched the Harlem Hospital Injury Prevention Program. Initially, they wanted to address an increase in gunshot wounds. “Fortunately,” Davidson said, “we did a survey of what people in the community wanted.” The real need, they discovered, in this section of the city plagued by drug dealers and drive-by shootings, was for safe places for children to play.

They answered that call by galvanizing community support. A coalition of small businesses, churches, other nongovernmental organizations, and the hospital fielded the first Little League the area had had in 30 years, basing it at the Charles Young Playground, the first of around a dozen of the largest play areas in Harlem that together they renovated. Thanks to a grant from the CDC New Injury Program, which allowed her to track serious injuries before and after the playground interventions, Davidson was able to document the program’s effect on lowering childhood injuries. And she learned well the importance of working in teams and across sectors.

A Broader Horizon

Davidson went on to expand her perspective through her international work—at a rural clinic in Guatemala, screening children for disabilities in Bangladesh and Pakistan, and, on a different scale than her work in small communities, on a regional and national level within the National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit in the United Kingdom. After a decade living abroad, she returned to New York, where through Columbia University she became involved in a community-based program preventing dating violence and youth violence.

Then, in 2003, her mentor got her involved in studying child disability in South Africa. At that time, the South African government did not acknowledge that HIV was a virus and did not support any emerging treatments, including interrupting maternal transfer of HIV. Among the Zulu people, children had the highest rate of juvenile HIV in the world. Around half of them died before their 5th birthday.

Davidson’s team enrolled 1,600 children, 90 percent of the population, in an observational study, evaluated them for disability, referred them for health services, and have followed them as they’ve grown. Now Davidson is the principal investigator of the study, and the children are adolescents. What they’re studying are social as well as medical conditions: risky sexual behavior and substance abuse. Davidson and her team are also working with the local department of education to try to establish cognitive screening within schools to identify students at risk of failing in this area with high dropout rates.

“I learned that working in teams is essential to bringing any change,” Davidson said, “that to protect children, the work has to be multisectoral, has to interlink with the communities. We have to work with health and education and social services, and also housing and transportation. And that that’s possible—that those alliances, those collaborations, can be built and can be effective.”

When she was younger, Davidson said, she assumed that gains made in human rights would be stable. “The horrible realization in the last six years has been that they’re getting reversed,” she said. “So we have to continue to fight.”

Read More

Leslie Davison ’66 visited Concord Academy in person in November 2021. She attended classes and spoke with students about her work. Read about her on-campus presentation here.

Leslie Davidson ’66 has devoted her life to researching disabilities in children, international child health, screening, epidemiology, and prevention of accidents and violence, particularly intimate partner violence. She has worked on an international team that developed an efficient approach to screen children for disabilities in developing countries and, for five years, led the Central Harlem School Health Program, launching childhood injury surveillance in Northern Manhattan linked to the development and evaluation of the Harlem Hospital Injury Prevention Program. Davidson moved to England in 1992 to work in the National Health Service as a pediatric epidemiologist and served as senior lecturer in pediatric epidemiology and public health at King’s College, London. In 1997, she became director of the National Pediatric Epidemiology Unit at Oxford. She returned to Columbia’s Mailman School in 2002 as chair of the Heilbrunn Department of Population and Family Health. She is a senior member of the Department of Epidemiology, director of the newly emerging Center for Child and Family Life Epidemiology, senior health advisor to Project THRIVE of the National Center for Children in Poverty, and director of the dating violence program of the Center for the Prevention of Youth Violence.

Ingrid Walker-Descartes ’91

In her presentation for the CA community, Walker-Descartes, a pediatrician with a specialty in child abuse and neglect, shared a case study to illustrate the importance of her work. It wasn’t about one of her patients. It was about herself.

An immigrant to the United States and the result of a teen pregnancy, Walker-Descartes had significantly higher odds of dropping out of high school and of giving birth herself before the age of 18 than peers with older parents. Statistically, she was also more likely to grow up in a family headed by a mother only, live in a poor neighborhood, and experience risks to her health and educational achievement. “The odds continue to stack,” she said, for significant disadvantage to children within Black immigrants, single-parent households.

But the adolescent years of this subject were very different from what might be expected. Walker-Descarte described the interventions “that ensured that, despite the negative statistical loading of a child with her background, the adversities faced by this child, or adolescent, were not her destiny.” They included the A Better Chance Program, which identifies, recruits, and develops leaders among young people of color throughout the United States. And by extension, through this educational referral organization, they also included Concord Academy.

As Walker-Descartes said, those interventions came with “side effects.” Research has shown that Black students at predominantly white independent schools often experience marginalization and feel underrepresented in the school culture and curriculum, and that these challenges can impact self-esteem, stress levels, self-efficacy, and aspects of identity development, as well as students’ academic functioning and social adjustment. Despite those challenges, many Black students still demonstrate resilience and academic success in these environments.

“What separates me from many of the children that I serve are merely circumstances,” Walker-Descartes said. “I am a true believer that adversity is not destiny. I am an example.”

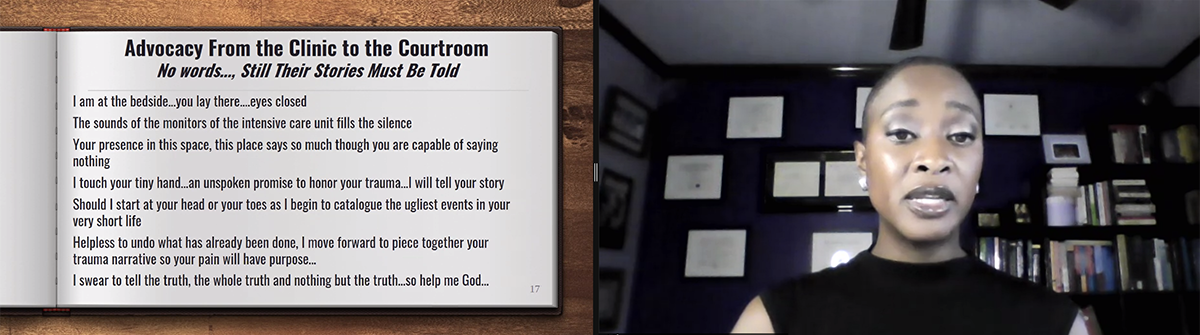

From the Clinic to the Courtroom

Walker-Descartes’ work in pediatrics focuses on adverse childhood experiences (or ACEs). The effect of traumatic experiences—abuse, neglect, or household disfunction—before the age of 18 are profound. Individuals who reported six or more ACEs have an average life expectancy two decades shorter than those who report none. ACEs increase the likelihood not only of children injecting street drugs, becoming an alcoholic, and contracting HIV, but also of committing suicide as an adult and becoming a victim of sexual assault.

“Nothing is necessary about trauma, especially with the children that I work with,” Walker-Descartes said. In her specialty of child abuse pediatrics, she makes interventions to alter the likelihood of adverse outcomes while children are experiencing ACEs. Her approach is one of multipronged advocacy.

Realizing that her skill set as a physician and researcher would not suffice to serve the needs of vulnerable children and families, Walker-Descartes earned a master of public health degree to impact policy and shape the delivery of medical care. In doing that work, she came to understand that, as she said, “the child protection system, designed to address the needs of vulnerable children and families, remains mired in bureaucracy and biases.” Indeed, as she experienced, it is often necessary to protect children and families from that very system—one that families, particularly from BIPOC communities, can become entangled in after mere accidents.

When Walker-Descartes came to understand that interventions fall short without the financing of health care for children, she went on to earn a master’s of business administration, becoming a clinician administrator and running a residency program and a fellowship program in child abuse pediatrics.

“Success,” in many of Walker-Descartes’ most emotionally wrenching cases, is a concept difficult to define. She has testified, for example, on behalf of infants who have not survived their abuse. “Advocacy, for me, goes from the clinic to the courtroom,” she said. “In speaking for children who are unable to do so, my team pieces together what happened to them, so that the parties responsible can be held accountable.”

What she said she most hopes for in her work is “to be that intervention to derail the negative trajectory of ACEs” for her patients. As she said, “This is how I pay it forward.”

Ingrid Walker-Descartes ’91 has dedicated her career to serving children as a pediatrician with a specialty in child abuse and neglect. A training faculty for residents at Maimonedes Hospital in New York, she graduated from the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry in 2001. Walker-Descartes is active in research and has authored several publications and educational materials. Her academic appointments include a Health Resources and Services Administration clinical research fellowship in general academic pediatrics at Mount Sinai School of Medicine, where she is also an instructor. She co-chairs the Child Protection Committee and the American Academy of Pediatrics Chapter 2 Committee on the Prevention of Family Violence. A member of the American Academy of Pediatrics, the Ambulatory Pediatric Association, and the AAP Special Interest Group on Child Abuse and Neglect, she is also an APA New Century Scholar Junior Mentor and a faculty scholar at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine Office of Ethnic and Multicultural Affairs. Walker-Descartes has received numerous honors, such as the Woodward Scholarship of the Office of Ethnic and Multicultural Affairs, the Medical Society of the State of New York Community Service Award, the Fannie & Henry Rice Scholarship, and the Rochester Prize Scholarship. She also volunteers for the Organization for International Development, which provides medical outreach to underserved communities in Jamaica without access to healthcare.

Watch the 2021 Joan Shaw Herman Award presentation by Dr. Leslie Davidson ’66 and Dr. Ingrid Walker-Descartes ’91 in full below.