Alumnae/i in the field see the AI revolution through a human lens

by Heidi Koelz, illustration by Chris Gash

You might encounter artificial intelligence (AI) a dozen times a day — talking with a chatbot, using a voice assistant, unlocking a smartphone with facial ID, or seeing a targeted ad. The dizzying rate of AI’s adoption, mostly behind the scenes, has meant that wariness has accompanied increasing public awareness. The AI almost all companies are developing today is not artificial general intelligence spanning multiple domains but rather artificial narrow intelligence focused on specified tasks: predicting equipment malfunctions or aiding a diagnosis, managing loans or driving a car. The industry is still young and largely unregulated, but AI has already proven its business value. Here, four Concord Academy alumnae/i discuss the technology’s potential, as well as the urgency of considering human outcomes and unintended consequences as it develops.

Cam Crary ’03 remembers as “transformative” the first time he stepped into one of Google subsidiary Waymo’s driverless vehicles. “You’re waiting on the side of the curb, you’ve hailed your ride, and when you get in it’s just you in the back,” he says. “You take off, and the car is stopping at traffic lights and yielding to pedestrians. It’s pretty magical.” The appeal of fully automated cars surpasses the novelty of the ride. Crary considers them “one of the most compelling use cases for AI,” given the stubbornly high incidence of highway fatalities. “It’s an example of taking an incumbent technology that is inherently unsafe and improving safety by having machines do a task that humans don’t do very well,” he says.

Crary has worked for Waymo, in Mountain View, Calif., since 2009. Hired to help establish safety and driving policies for test operators, he now works with cross-functional teams to determine performance specifications, define test methodologies, and review code health and engineering and risk-management processes. Waymo has spent many more hours than its competitors test-driving its vehicles. “My team and I craft a narrative for why we believe the system is ready for safe operations on public roads without a driver,” Crary says.

In 2017, the company rolled out several hundred fully automated vehicles to “early riders” within a small test area of Phoenix. What Crary regarded until recently as “a fascinating research project” will soon, he predicts, be in broader use as public rides start to become available. “It will be a huge growth experience to take that step into having real accountability for people’s lives,” he says.

Within his industry, he expects to see expert development of regulatory and safety standards catch up soon. Crary knows trust is paramount. “It will determine the success or failure of the technology,” he says. “What we really want to see is, does this car drive like a human and do you trust it as you would a human driver?” In considering other AI applications, though, Crary is more cautious. “For example, when people want to use AI to help determine when incarcerated people get released, the hope is that it’s a less biased decision, but it doesn’t take much to imagine that every unjust bias of the builders is going to be built in,” he says. “That’s a problem that may be better solved through structural changes and policy solutions.”

“What we really want to see is, does this car drive like a human and do you trust it as you would a human driver?”

– Cam Crary ’03

Google subsidiary Waymo has already launched a fleet of fully automated vehicles within a small test area of Phoenix. Photo courtesy of Waymo.

Participants in Waymo’s Early Riders Program experience a driverless ride. Photo courtesy of Waymo.

The Purpose of AI

In 2011, as a sophomore at Tufts University, Alex Ocampo ’10 watched IBM’s Watson trounce two all-time Jeopardy! champions — precisely what the supercomputer had been designed to do. Just three years later, Ocampo and a cohort of other recent college graduates joined IBM’s Watson Group, soon after it formed in 2014. “We were all ready to use AI to change the world and solve big problems,” he says. By then, Watson had grown into a cloud utility system that learns from experience through an array of artificial intelligence techniques spanning speech, vision, language, and data analysis — one depended on around the globe and in virtually every industry.

“AI is not magic. It’s advanced computer science and advanced math, and there are people behind it.”

– Alex Ocampo ’10

Ocampo has developed public-sector AI applications for national security, law enforcement, social programs, and education. Now he helps all sorts of clients at IBM Watson Experience Centers in San Francisco, New York, and Cambridge, Mass. understand AI’s potential. He addresses a common fear about automation: “A principle I really believe in is that AI is meant to augment human ability, not replace it,” he says. (Ocampo prefers the term “augmented intelligence” to “artificial intelligence.”)

“The purpose of AI is to extract meaning from unstructured data,” Ocampo explains. Strong tools, such as Excel, can understand structured data, but unstructured information — descriptions, audio, video, or images that get relegated to catch-all “Notes” spreadsheet columns — “that’s data that our machines haven’t historically been good at understanding and reasoning around,” he says. AI can understand that crucial context, to better support the human strengths of high-level, creative thinking.

“AI can help us make decisions based on more complete information,” Ocampo says. Take a practicing physician with limited time to read studies. “Doctors might see a treatment work once and come to rely on it, but they’re making assumptions without looking at the full picture of that patient or recent developments,” he says. “So bringing AI into this situation can result in improved treatment, more personalized treatment, instead of routines that rely on habits and biases.”

One bias he’s referring to is data bias: over- and underrepresentation in the data upon which decisions are based. Take a fuller data set into account with AI and you’re making better-informed decisions, in less time. Legal clients using Watson, for example, have reported spending only a few hours on contracts that previously took them days or weeks to review.

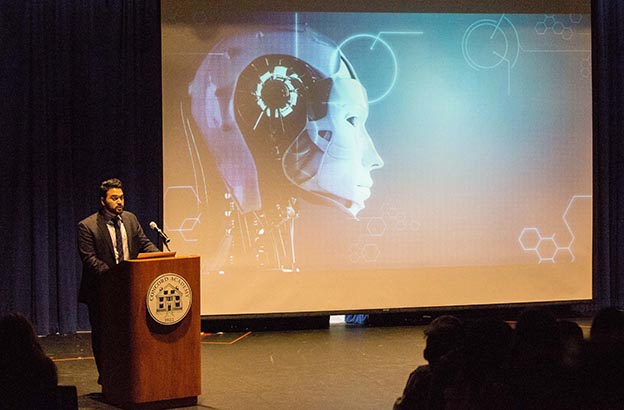

Alex Ocampo ’10 speaks at an assembly at Concord Academy in 2018.

Ocampo cautions, however, that the quality of AI is only as good as its data. “If there isn’t enough representation in use cases, you won’t get good output,” he says. “Two of the biggest obstacles to good AI are access to clean data and the transparency of what’s being done with it.”

Lack of transparency leaves AI vulnerable to another type of bias: social prejudice. A 2018 MIT Media Lab study showed that, across three major commercial facial recognition applications, accuracy in identifying gender varied wildly, with an error rate of less than 1 percent for light-skinned men and nearly 35 percent for dark-skinned women. Skewed data sets were found to be a factor.

But in monitoring for bias, AI can help too, Ocampo points out. IBM, for example, created the Watson Open Scale platform to test every variable input for bias while decisions are being made, highlight risk factors in data sets, and recommend adjustments. The goal: an explainable model.

“AI is not magic,” Ocampo says. “It’s advanced computer science and advanced math, and there are people behind it.” He’s encouraged by an increasing focus on ensuring unbiased data through such corrective feedback. Ocampo has advice for AI developers: “Look around the room. Who’s represented, and who’s not? Get other people in there — that’s how you protect yourself from these shortcomings in data.”

Lifting the Lid on the Black Box

In his 10 years working on the business side of the AI industry, including at Domino Data Lab, DataRobot, and now Texas-based SparkCognition, Scott Armstrong ’96 has seen AI’s tremendous value for customers. Predictive maintenance solutions, for example, can anticipate up to two weeks in advance when machinery will break, eliminating costly downtime. And one financial client recently saved $100 million by implementing an AI product. “It’s astonishing how much this is worth,” Armstrong says.

There’s also real human value, he adds. Recent studies have demonstrated increased accuracy in mammography interpretation and lung cancer detection when AI is used in conjunction with radiologists. Or consider sepsis, which kills almost 7,000 children annually in the U.S., according to the Sepsis Alliance. Early treatment can save lives, but it’s notoriously difficult to diagnose. In November 2019, a team at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus developed an algorithm that predicted septic shock accurately in 90 percent of its study’s pediatric cases, and earlier than existing models. “Having a machine take variables on a chart and get an accurate diagnosis is doing something that is beyond our human capacity right now,” Armstrong says.

With ransomware attacks a growing problem, cybersecurity is another major focus for AI solutions. Typical security products create thumbprints of code anomalies, and there could be a lag of a day or a week before fixes are pushed back. But with SparkCognition’s homegrown AI built in, “the fix is already in place,” Armstrong says. “If anything abnormal is going on, it will just stop,” even in air-gapped computers that, for security, aren’t connected to the internet. The implications are great for national security and defense.

Armstrong explains that AI products require access to historical data “so that models can be trained for accuracy on known outcomes before they’re deployed.” AI applications have surged as the costs of analyzing, storing, and processing data have plummeted. While many possibilities are promising, he says that how that data is being gathered and handled should bear scrutiny.

“The good thing is that people are still figuring this out, and it’s earlier than you think it is. There are opportunities right now to put processes in place to make it a more regulated industry.”

– Scott Armstrong ’96

The data scientists who create predictive algorithms work on separate teams from the developers who put them into production. “Data scientists are thinking about how to make money, and they aren’t necessarily concerned with compliance or how to explain a model to, say, someone whose loan was not approved,” Armstrong says. “They don’t start with those parameters upfront.” He considers the current focus within the industry on “explainable AI” a positive development in response to the problem of “black-box solutions”: complex AI models whose decisions can’t be questioned because the process is concealed.

“The good thing is that people are still figuring this out, and it’s earlier than you think it is,” Armstrong says. “There are opportunities right now to put processes in place to make it a more regulated industry.”

Speaking the Same Language

Andrea Cross ’90 wanted to work for the Partnership on AI (PAI), she says, because “AI touches almost every single aspect of society today.” She joined the San Francisco-based nonprofit organization in June 2019, bringing her passion for sharing stories about science and her experience as a film producer to help figure out how AI can be used effectively and appropriately.

PAI is a coalition of more than 100 partners, including six of the world’s largest tech companies — Amazon, Apple, DeepMind, Facebook, Google, and IBM — as well as academics, media companies, and nongovernmental organizations such as the ACLU, Amnesty International, and Human Rights Watch. Although PAI doesn’t regulate or lobby, its multistakeholder process produces resources for policymakers as well as industry practitioners.

Open dialogue, in the same physical space, is central to PAI’s approach. “It’s about listening and coming to understand what the problems are,” Cross says. “This is a unique organization that has this combination of industry partners and civil society organizations in the room at the same time, with the goal of bringing voices from underrepresented communities directly to computer scientists and programmers, to make sure that they’re aware of the unintended consequences of AI and how to improve the transparency of how AI is developed and implemented.”

“AI is becoming more and more integrated into everyday life, so how do we think it through? We need to be thinking in a more human framework.”

– Andrea Cross ’90

Last year, PAI documented the serious shortcomings of relying on algorithmic risk assessment for criminal justice decisions, such as whether to detain suspects or extend prison terms. Its report outlines 10 requirements for responsible deployment by jurisdictions, which are largely unfulfilled. “Although the use of these tools is in part motivated by the desire to mitigate existing human fallibility in the criminal justice system, it is a serious misunderstanding to view tools as objective or neutral simply because they are based on data,” it states.

This February, following the release of the European Commission’s plan to regulate artificial intelligence — which includes banning black-box systems, requiring AI to be trained on representative data, and calling for broad debate about facial recognition technologies — PAI published a paper intended to help policymakers and the public use the same terminology in understanding how facial recognition systems work. Cross produced an interactive infographic for the PAI website that explains the systems’ mechanisms and demonstrates how altering parameters can result in false positive or false negative facial matches.

“What we’re saying is, let’s have a baseline for how we can talk about the issues so there can be a productive discussion about the roles of these systems in society,” Cross says.

Decisions about corporate accountability, privacy, and informed consent ultimately reside with regulators. For now, PAI will continue offering information so that governments, businesses, and individuals can see a fuller picture — much like the one AI itself aims to provide.

That broader view encompasses both the great possibilities AI is opening up and its real consequences in people’s lives. “AI is becoming more and more integrated into everyday life, so how do we think it through?” Cross says. “We need to be thinking in a more human framework.”