Rather than taking a day off for Martin Luther King Jr. Day, each year Concord Academy commemorates the life and legacy of Dr. King by spending the day engaged in social justice discussion and work. On January 21, a full day of programming by the Community and Equity Office gave the CA community an opportunity to step outside of the regular academic routine to consider our own identities, the societies we live in, and the future we want for ourselves and for others in our communities.

As Head of School Rick Hardy said in his opening remarks, it was a day “to listen, to reflect, and to learn together, to try to understand the world from another person’s point of view, and to understand ourselves and our impact on those around us.” Reflecting on a passage from Dr. King’s Letter from Birmingham Jail, which laments the “appalling silence of the good,” Hardy acknowledged a “comfortable sort of hope” that his own privilege affords him, that injustice will somehow wither on its own. He urged CA students to remember that “this work of building a better world is not inevitable — it required each of us and all of us.”

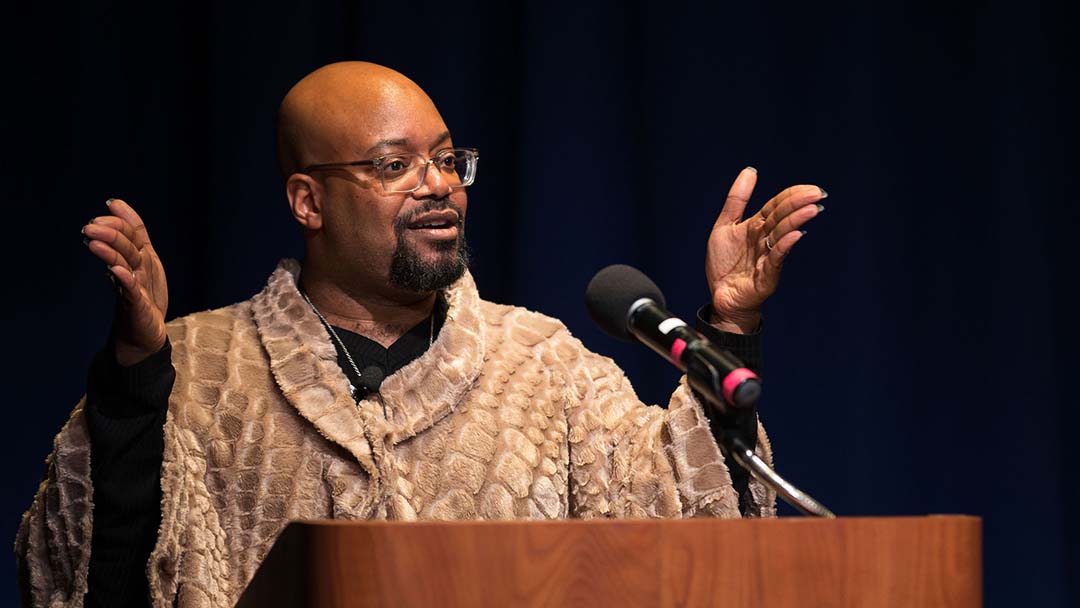

Keynote Address

The highlight of the day was a keynote address by Rodney Glasgow, a respected and charismatic educator, speaker, facilitator, trainer, and activist in the areas of diversity, equity, and social justice. Among other leadership roles, Glasgow serves as the chief diversity officer and head of the middle school at St. Andrew’s Episcopal School and is a founding member and chair of the National Association of Independent School’s annual Student Diversity Leadership Conference, which draws more than 1,500 high school students nationwide each year.

Glasgow was asked to speak at CA about what it means to be himself — a black, gay man — in America today. In discussing black masculinity, Glasgow examined his personal history to call attention to broader societal conditions. In doing so, he set an example for using the material of our own lives to illuminate the lives of others, because, as he said, we have to start being able “to tell our stories and to receive each other’s stories in an authentic way.”

Glasgow’s stories of black manhood began in the West Baltimore ghetto where he was born to a teenage mother in 1979, three months prematurely and confined to an incubator for the first 90 days of his life, waiting for human touch. Whether you’re born only 3 pounds or not, he said, that is a black man’s story: “You walk around in life waiting for someone to be allowed to show you some care.” Glasgow talked of his mother’s resolve in the face of a grim prognosis when he contracted pneumonia at just 2 years old — the doctor told her she couldn’t save him, only make him comfortable. That too, Glasgow said, is a black man’s story. His mother prayed for him not just to survive but to thrive, and he did, going on to earn two degrees from Ivy League universities so that his voice might matter in the world in ways hers hadn’t.

In language both open and poetic, Glasgow talked about the layers of history it’s all too easy to walk through unaware — eating as a child at the Woolworth lunch counter 25 years after the civil rights protests, working now at a school built in a historically white neighborhood, living now just around the corner from a site of the Underground Railroad.

He spoke of how black men in white spaces don’t choose to see each other, and of their complicated relationship with white men, regardless of their sexuality. Poignantly, Glasgow spoke of his early crushes on white boys, the first in kindergarten. One of only a few black boys deemed “gifted” in the public school system, in middle school he began attending an independent, overwhelmingly white all-boys school thanks to the intervention of his white elementary school teacher. He became infatuated with an older white boy, a wrestler, when he was in eighth grade. The boy terrorized him privately, deeply, mercilessly, about his sexual orientation. “I never learned to hate him for it,” Glasgow said. “I learned to fear him and hate myself.”

A few years ago, Glasgow learned of that boy’s death. A former teacher told him it made sense that he had been the target, because he had been himself, and comfortable, and powerful, as that boy had only appeared to be. He also learned that the boy may have had a harder life than Glasgow knew. “The world gave me a gift that day, and the gift was seeing the humanity in the person on the other side of the fence — the person who was my main tormentor was also a human being with his own story and his own struggles,” he said. “But isn’t that the story of black men, that we have to see the humanity in the people degrading us?”

Glasgow spoke of an interaction with police, unprompted by any reasonable suspicion, that shook his adopted son, and another that had shaken him. And drawing on the example of Sojourner Truth, he asked about black, gay manhood, “And ain’t I a man?” He compared himself to white men who can walk down the street powerfully without fear, earn notice and respect even if they don’t deserve it, and walk in public hand-in-hand with their loved ones. “Those men have a country that will fight for them and protect them,” he said, powerfully. “I have a country that abuses me and asks me to love it back. The work we have to do is real.”

Film

Adrian Balvuena ’19 and Andreas Byamana ’19 introduced a showing of Brother Outsider: The Life of Bayard Rustin by filmmaker Nancy Kates ’80, part of the yearlong 30th-anniversary celebration of Concord Academy’s GSA (the gay-straight alliance now known as the Gender Sexuality Alliance). The architect of the March on Washington and the dreamer behind Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech was, as a black, gay man, was marginalized as a lesser-known hero in the fight for civil rights. The film was shown with the hope of celebrating his intersectional identity and ensuring that everyone will know his name.

Workshops

Throughout the day, workshops planned and facilitated by students and faculty alike engaged the community in deep consideration of topics as diverse as white privilege and anti-racism; racial, gender, and class representation in music; microaggressions and what it means to be Asian or Asian American; the news media’s effect on political and social justice movements; discrimination facing women in tech; and intersectional identity exploration and deep listening. CA theater teacher Shelley Bolman’s company Theatre Espresso once again came to campus to perform the interactive drama Justice At War: The Story of the Japanese Internment Camps.

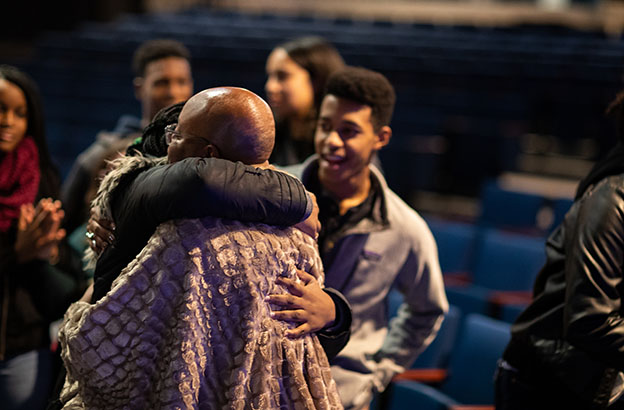

The energy in the P.A.C. at the close of the program, following Glasgow’s keynote, was palpable. The students jumped to their feet with applause, and many lingered afterward with questions. Having taken the day to share openheartedly and listen carefully and with compassion, they were ready to engage.