Photo courtesy of Drew Gilpin Faust ’64

When U.S. Rep. John Lewis, a legendary civil rights activist, addressed graduates at Harvard’s 2018 commencement, he turned to Drew Gilpin Faust ’64 and thanked her for her leadership, for “getting into trouble, necessary trouble, to lead this university,” and for using her office to “move Harvard toward a more all-inclusive community.” It was Faust’s final commencement as Harvard’s first female president, a role she had held since 2007.

“Necessary trouble” was a phrase Lewis, who died in 2020, used often to describe the good kind of trouble brave, compassionate people make for the sake of justice. He gave his blessing for Faust to use the phrase as the title for her deeply engaging new memoir, Necessary Trouble: Growing Up at Midcentury.

This coming-of-age story, her seventh book, ends long before Faust’s successful tenure at Harvard. The memoir covers the years from her childhood on a Virginia farm to her graduation from Bryn Mawr in 1968. It was a privileged upbringing, accompanied by the expectation that she would become a Southern belle. “I was urged to lower my voice, not to speak ‘like a fishwife,’ to soften my insistence, not to be so bossy, to defer more to others,” she writes.

The “necessary trouble” started early, as Catharine Drew Gilpin rebelled against such strictures and found herself at odds with a mother who had curtailed her own aspirations in favor of becoming what the era demanded of an “ideal” wife and mother.

With her keen historian’s eye, Faust blends her personal struggles to grow into the woman she wants to become with her young self’s growing awareness of the broader issues that came to define postwar America. “History is about choices and what those choices looked like to one girl trying to become a person during two decades of rapid transformation and powerful reaction in American life,” she writes in her prologue. “It was a time when new possibilities opened doors and paths my mother and grandmothers could not have imagined … a time when ideas and even movements were emerging to challenge assumptions about race, gender, and privilege … a time that inaugurated many of the changes—and divisions— we grapple with still.”

“Drewdie” Gilpin arrived at Concord Academy in 1960, a few days before her 13th birthday. She was drawn to the school in part, she says, because she’d been told the punishment for lateness was chopping wood, a practice she saw as both useful and effective. Welcomed warmly by her fellow boarders and by teachers who flouted the societal rules imposed on women, she enjoyed being at “a school where girls were what mattered, and where their intellects were reinforced and rewarded.”

As was true for so many students of that time, Headmistress Elizabeth B. Hall P’85 exerted a strong influence on Faust during her years at CA. “I admired her for being ‘simply true,’” she writes. “It was hard to imagine what she could not do. She took us seriously, urged us to think about Big Questions, and recruited us into a moral strenuousness intended to be the basis for a considered life. She was a combination of Socrates and General Patton.”

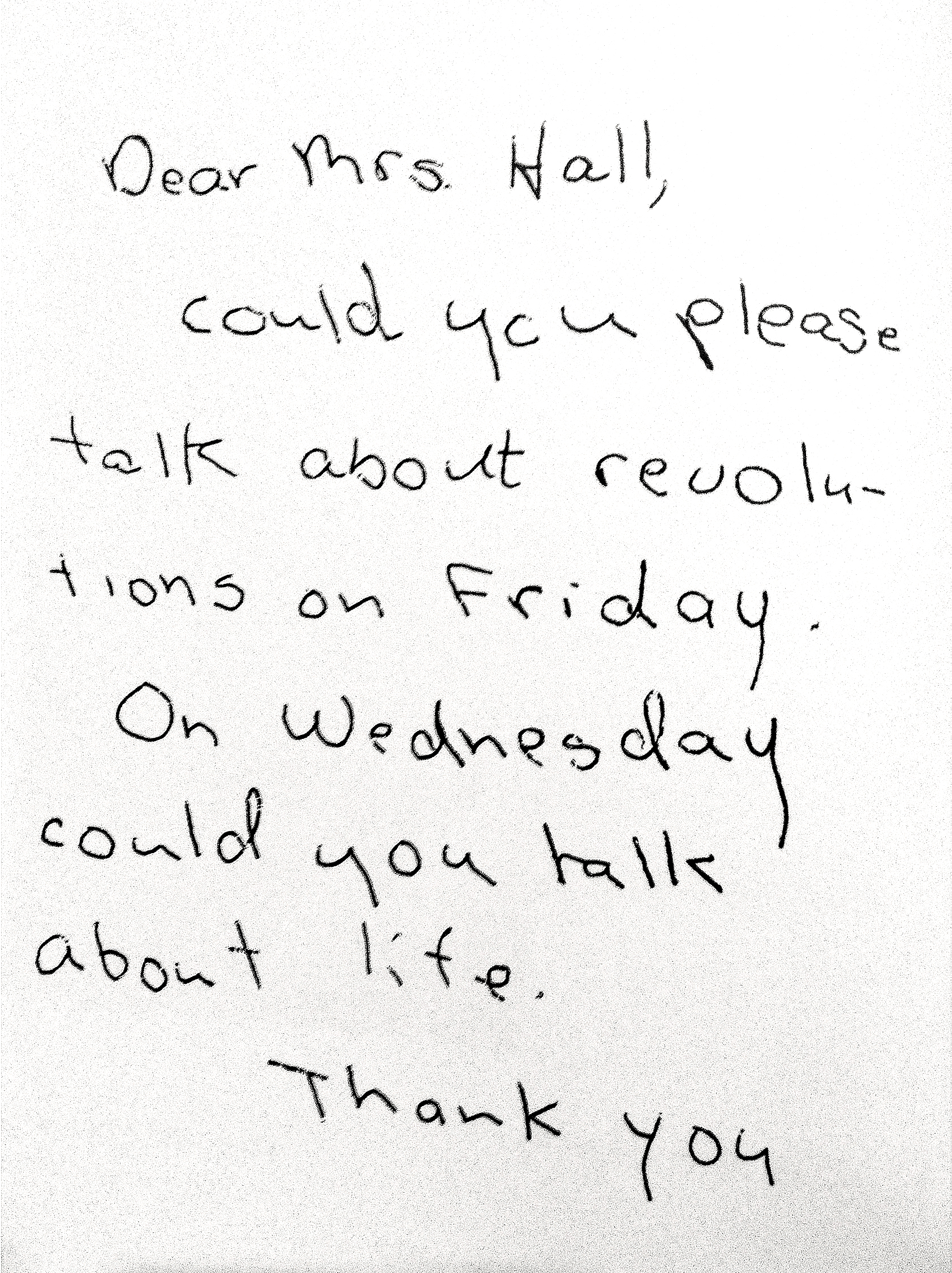

A note from a Concord Academy student to Headmistress Elizabeth B. Hall, which Faust reproduced in her memoir. “When Mrs. Hall asked what subjects we would like her to address in her chapel and assembly talks, this was one response,” she wrote.

The chapter Faust devotes to her Concord Academy experience offers insight into the social and academic life of the school during the start of a transformational decade. “In fundamental ways, Concord was a bubble,” she writes. “A bubble for white Anglo-Saxon Protestants. A bubble in which men were scarce and women ruled. But we could hardly hide from the world and the accelerating changes and crises all around us. The school urged that sense of responsibility on us, and the state of the world made it seem imperative.”

Faust had brought a strong sense of social responsibility with her; at the age of 9, she had written a letter to President Eisenhower expressing her dismay at racial segregation. Her CA years only served to bolster her sense of justice and became a launching pad for her early activism. She chronicles a summer trip to Eastern Europe between her junior and senior years at Concord, and another through the southern states shortly after her graduation at age 16. These travels raised her awareness of global issues and persistent social injustices.

Notably, while a freshman at Bryn Mawr, Faust chose to leave her classes behind for “four momentous days” in 1965 to participate in the historic march from Selma to Montgomery, Ala., led by Martin Luther King Jr. That choice got her into trouble with her English professor, who wrote a scathing critique of her hastily drafted essay handed in by a friend during her absence.

But that was necessary trouble, the kind Faust would continue to engage in as a distinguished scholar and university president, the kind she remembers Mrs. Hall endorsing when the much-admired “Head Mischief” would tell students, “Function in adversity. Finish in style.”

—Lucille Stott