The coronavirus pandemic has made the U.S. health care system’s faults more visible, but young medical professionals are redoubling their commitments to serving those in greatest need

Story By Heidi Koelz Illustration By Anna & Elena Balbusso

On March 10 at Elmhurst Hospital in Queens, N.Y., Fred Milgrim ’08 swabbed his first patient suspected of having COVID-19. The following day, the emergency resident physician traveled to attend a wedding. By March 16, when he returned, the emergency department had been reconfigured: Multiple large areas had been walled off into airborne isolation units.

Over the following week, the enclosures overflowed with patients who had the virus. Even with two-thirds of the emergency department filled with COVID-19 patients, Milgrim knew cases were slipping through the cracks — disguised as acute kidney failure, heart attacks, or arrhythmia. The disjunction between seeing New Yorkers out on sunny spring days as he bicycled to work and what he calls the “hellscape” that awaited him at the hospital was hard to reconcile.

That’s when Milgrim, previously a journalist, sounded an alarm. “China warned Italy,” he wrote in an essay published on March 29 in the Atlantic. “Italy warned us. We didn’t listen. Now the onus is on the rest of America to listen to New York.” His article led to a CNN interview with Anderson Cooper, but Milgrim didn’t respond to other media requests. Instead, in June, he began editing for Brief19, a daily digest of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 research and policy started by a former colleague, helping to share authoritative information about COVID-19 with other doctors and the public.

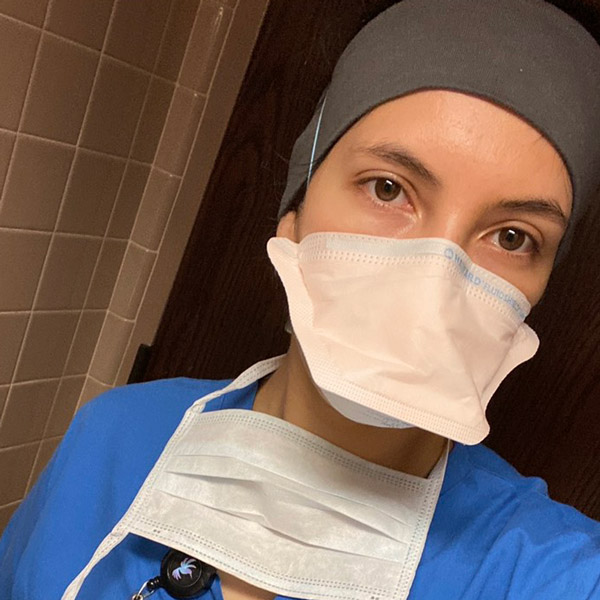

Fred Milgrim ’08

Pictured in March before his shift as an emergency resident physician in the Elmhurst Hospital emergency department in Queens, N.Y. He commutes by bike over the Queensboro Bridge.

As a resident at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, Milgrim rotates at two hospitals in Manhattan and at Elmhurst, in Queens, where he witnessed the disproportionate devastation of the Jackson Heights neighborhood. He considers Elmhurst “an incredible place to train and work.” It’s the clinical setting that most interested him when he was considering residency programs. When the media negatively compared patient care during the pandemic at Elmhurst, a public hospital, with private institutions, he took offense. “We have the same residents, the same capable doctors and nurses taking good care of patients, but the outcomes are different for so many reasons,” Milgrim says. “City hospitals are inundated with sick, uninsured people without access to primary care, affected by systemic racism, suffering from unequal wealth. We have such a robust emergency medicine practice in this country out of necessity. The ER is our answer to public health — for a lot of people, we are it.”

A 2019 graduate of the Boston University School of Medicine, Milgrim belongs to a generation of young medical professionals who were just finding their footing in the chaotic world of emergency medicine when the pandemic began. He says being a first-year resident was “probably the best time” to encounter the turmoil: He had enough experience to meet the demands of the crisis, and he needed, and found, opportunities to improve his skills. “There weren’t enough hands to do critical procedures, so we got to be involved in a lot more than even more senior colleagues,” he says.

“We have such a robust emergency medicine practice in this country out of necessity. The ER is our answer to public health — for a lot of people, we are it.”

—Fred Milgrim ’08

Kara Huston ’03

Emergency physician Kara Huston ’03, her face marked by the personal protective equipment she wears in the ER in New Bedford, Mass.

The pandemic has tested what emergency medicine professionals can bear, even as they affirm their commitment to caring for all who come through the ER’s doors. In New Bedford, Mass., emergency physician Kara Huston ’03 works for Beth Israel, staffing the ER at St. Luke’s Hospital. She appreciates the “energy and teamwork” in the emergency department, she says: “I like building rapport quickly. I like taking care of people, and I like puzzles. It’s a hard job, but I find it very rewarding.”

The U.S. health care system, how- ever, leaves her baffled. Like Milgrim, she says emergency departments end up offering care that could be better provided elsewhere, such as for psychiatric patients. “There are so many smart, hardworking, caring individuals, but people in health care know that at every layer — not just insurance — the system is a patchwork that doesn’t work,” she says.

COVID-19 exposed the gaps. Initially, Huston says, staff at her hospital were discouraged from using masks in an effort to preserve supplies. Slowly, it became clear that everyone interacting with patients should have an N95 respirator. But, as at hospitals across the country, St. Luke’s staff had to reuse them time after time. When Huston was provided gowns labeled “not for medical use,” she purchased her own personal protective equipment (PPE). “There’s a huge difference when a hospital is run by a physician,” she says. “Most hospitals aren’t, and their priorities are different than those established with a doctor’s mindset.”

As traumatizing as battling the pandemic has been, Huston has been most affected by what she’s unable to do for non-COVID patients. New protocols to limit the spread of the virus include banning standard aerosolizing treatments, for example.

This summer, rather than using a nebulizer as usual, Huston injected a woman with severe asthma with epinephrine — the treatment of last resort worked, but it was the first time she had ever attempted it. “It’s upsetting to have to just watch those patients who could turn around with everyday treatments that we’re now not allowed to use,” she says. “When you don’t feel like you know anything about a novel virus, it’s really taxing.”

Collaborating has been made harder by the isolation emergency medicine professionals have had to adapt to at work. Doctors have been exchanging strategies over social media, but their in-person interactions with colleagues have been radically altered. Huston’s

CA classmate Kimon Ioannides ’03, an emergency physician who works clinical shifts at multiple Los Angeles hospitals, says, “We don’t socialize in the same way now. We’re wearing masks throughout our 12-hour shifts. Now we go into a supply closet to take a drink, or out into the ambulance bay to eat a sandwich alone.”

When the coronavirus hit, well-resourced UCLA didn’t have as much difficulty securing PPE as other hospitals where Ioannides has worked. Still, he’s concerned for the custodial staff who have to clean rooms right after COVID-19 patients leave. “I knew what I might get into if there were a pandemic, but they didn’t,” he says. “We know that disease, as well as instability of all kinds, affects people really differently. We see that every day.”

Kimon Ioannides ’03

An emergency physician and fellow in the National Clinician Scholars Program at UCLA.

“The core of emergency medicine is taking care of anybody — and for us, that has always been and will always be disproportionately folks with fewer resources. That’s what we’re passionate about. In some ways COVID is no different, it’s just more visible.”

—Kimon Ioannides ’03

Ioannides is a fellow in the National Clinician Scholars Program at UCLA, whose goal is to train clinical researchers to act as change agents to improve health care and reduce health disparities. He’s researching which health conditions were most exacerbated as ERs across the country experienced a steep decline in visits this spring. Knowing systemic change will take time, he focuses on what’s within his control. “I think about my biases when I’m seeing patients, and how they translate to other providers,” he says. “A lot of them come out in charting and notes, in ways we pick up on before even seeing patients.”

The core of emergency medicine, Ioannides says, is “taking care of any- body — and for us, that has always been and will always be disproportion- ately folks with fewer resources. That’s what we’re passionate about. In some ways COVID is no different, it’s just more visible.”

Nurses and other critical health care personnel are facing the same conditions as doctors on the COVID-19 front lines, though often with more limited protections and recognition. A nursing assistant at Hackensack University Medical Center in New Jersey, Jazmin Londono ’12 works in a heart-failure unit that was converted to COVID-19 care in March, when PPE was in short supply, and she didn’t feel her safety was a priority for the hospital. Before it resumed its regular function in June, her unit cared for 26 COVID-19 patients at a time, with only two nursing assistants entering all 13 rooms. When travel nurses from other states arrived, she was grateful for their help but also conscious of how well they were being paid; Londono says she doesn’t earn a living wage.

“I’m the person there to listen to patients’ problems, to help clean them, feed them, and talk with them when they’re not feeling well, and relay all of it to the nurse,” Londono says. She has also assisted with videoconference calls for families, so they have a chance to see their loved ones during their final moments.

Many of her patients who have diabetes or heart disease lack the education or resources for eating well — and Londono says the vast majority of these conditions are preventable. “With good educators, patients can change their lives, but systemic inequality and oppression play a big part in their being sick in the first place,” she says.

Jazmin Londono ’12

A nursing assistant for heart-failure patients in Hackensack, N.J., found herself working on a COVID-19 ward this spring.

Londono wants to become a trauma nurse, and perhaps eventually train in psychology. “Patients are dealing with so much in this tragic time, not just with illness but with how to survive,” she says. “I want to be able to counsel people.” She takes pride in being able to use her Spanish language skills to put Spanish-speaking patients at ease, and she hopes for positive change in the medical system, she says, “for more empathy, because people becoming practitioners now are more educated and care more about a person’s whole well-being.”

Lindsay Klickstein ’15

Lindsay Klickstein ’15 finds her work as a medical scribe in a North Carolina ER good experience for medical school.

Starting their training at the low end of the hospital hierarchy may help future providers see that bigger picture. In North Carolina, Lindsay Klickstein ’15 works as a medical scribe, reviewing EMT records for doctors, writing patient records, and recording medical decisions. She moves among three UNC Health campus emergency departments, and she is also the emergency department site coordinator at UNC Health’s main hospital. Klickstein is a part of the medical staff more than she had anticipated, even helping to interpret imaging and lab results and assisting in response to strokes and traumas. Early in the pandemic, scribes weren’t issued masks, though now they wear them daily. The job pays minimum wage and provides no health insurance or paid time off.

Already certified as a wilderness emergency medical technician, Klickstein trained as a scribe for two months before going solo on March 3, a week before the World Health Organization declared the coronavirus outbreak a pandemic. After one ward at UNC’s main hospital was converted to a COVID-19 unit, more than a third of the scribes on staff quit. Klickstein stayed. She’s applying to medical schools this year and considers her work excellent training. “I love emergency departments,” she says. “I function well in a state of high intensity. In the ER, I feel really comfortable — I know what I can do to help, and that’s how I always want to feel. It’s what drew me to search-and-rescue, too. I’ve learned so much watching ER physicians tackle the pandemic.”

I function well in a state of high intensity. In the ER, I feel really comfortable — I know what I can do to help, and that’s how I always want to feel. I’ve learned so much watching ER physicians tackle the pandemic.”

—Lindsay Klickstein ’15

Benchize Fleuraguste ’12 also considers emergency medicine her passion. Since her first interaction with paramedics, who saved her mother’s life, she has wanted to work in health care. In the summer after her junior year at CA, she trained as an EMT. Now she attends a doctoral program in nursing while working as an emergency room nurse in the greater Boston area, with plans to specialize in MedFlight air transport critical care as well as to teach someday. Like Londono, she has found her facility with several languages helps reassure her patients.

During the pandemic, Fleuraguste has observed that people of color have been scared to come to the ER for treatment. Though she understands that often economic pressure and lack of education make access to health care difficult at any time, she thinks having more providers of color would help. “Patients are more apt to trust individuals who look like them and understand their culture, who can educate them in the same way they have learned,” she says.

Fleuraguste praises Massachusetts’ phased COVID-19 plan, but she’s incensed by the lack of U.S. leadership in a coordinated pandemic response. “This new virus is ever-changing, but we learned a lot from when Ebola hit and swift government action helped to tamp it down and prepare health systems,” she says. For her, the government’s failure is personal: She has lost family members to COVID-19.

“My family is concerned about my exposure at work, but a lot of them understand it’s not just a job,” she says. “It’s what I trained to do, and I love helping people. Not being there is not an option for me. I can’t sit back and leave my colleagues hanging. And we’re supposed to advocate for everyone, from all walks of life — that’s something I learned from CA.”

Benchize Fleuraguste ’12

Health care is her passion, and the pandemic hasn’t changed that.

—Benchize Fleuraguste ’12