Through Her Patients’ Stories, Oncologist Naomi Ko ’91, P’21 ’26 Makes Health Care Inequities Personal

When breast oncologist Naomi Ko ’91, P’21 ’26 visited Concord Academy on February 6, 2026, she spoke passionately about what she investigates: “Why do Black and brown women die of breast cancer at much higher rates than white women?” In a talk by turns historically informed and deeply personal, she offered the professional perspectives of both a researcher and a practicing clinician, as well as her own story of losing her grandmother to breast cancer.

“Cancer itself doesn’t discriminate, but the rest of the world does,” she said. “Living with the same disease, two hosts battle the tumor with wildly different circumstances, and their chances for survival can be vastly different. These differences are human-made, and they can be human-fixed.”

Her idealism is grounded in 22 years of experience in treating breast cancer patients. As the section chief of breast cancer medical oncology at NYU Langone Health, a role she began this year, Ko runs a translational research lab that investigates tumor biology and the social determinants of health. Previously, she taught and practiced for 14 years at Boston University and its affiliate hospital, Boston Medical Center. This “safety-net hospital” for the uninsured sits just 2 miles—but a world away—from the renowned Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, she said: “We serve wildly different patient populations, and the cancer experiences are as different as if we were in two different countries.”

Ko showed a map depicting the 1930s redlining that codified discriminatory mortgage lending with lasting effects on Boston communities. In largely affluent, white Back Bay, she said, only 15% of residents are enrolled in MassHealth, the Massachusetts state plan that provides free or low-cost insurance to low-income residents. In contrast, more than half to three-quarters of residents use Mass Health in Roxbury, Mattapan, and Dorchester, where two-thirds of Boston’s Black population is concentrated. Deep structural inequities correlate with a staggering 20- to 30-year difference in life expectancy between the two areas.

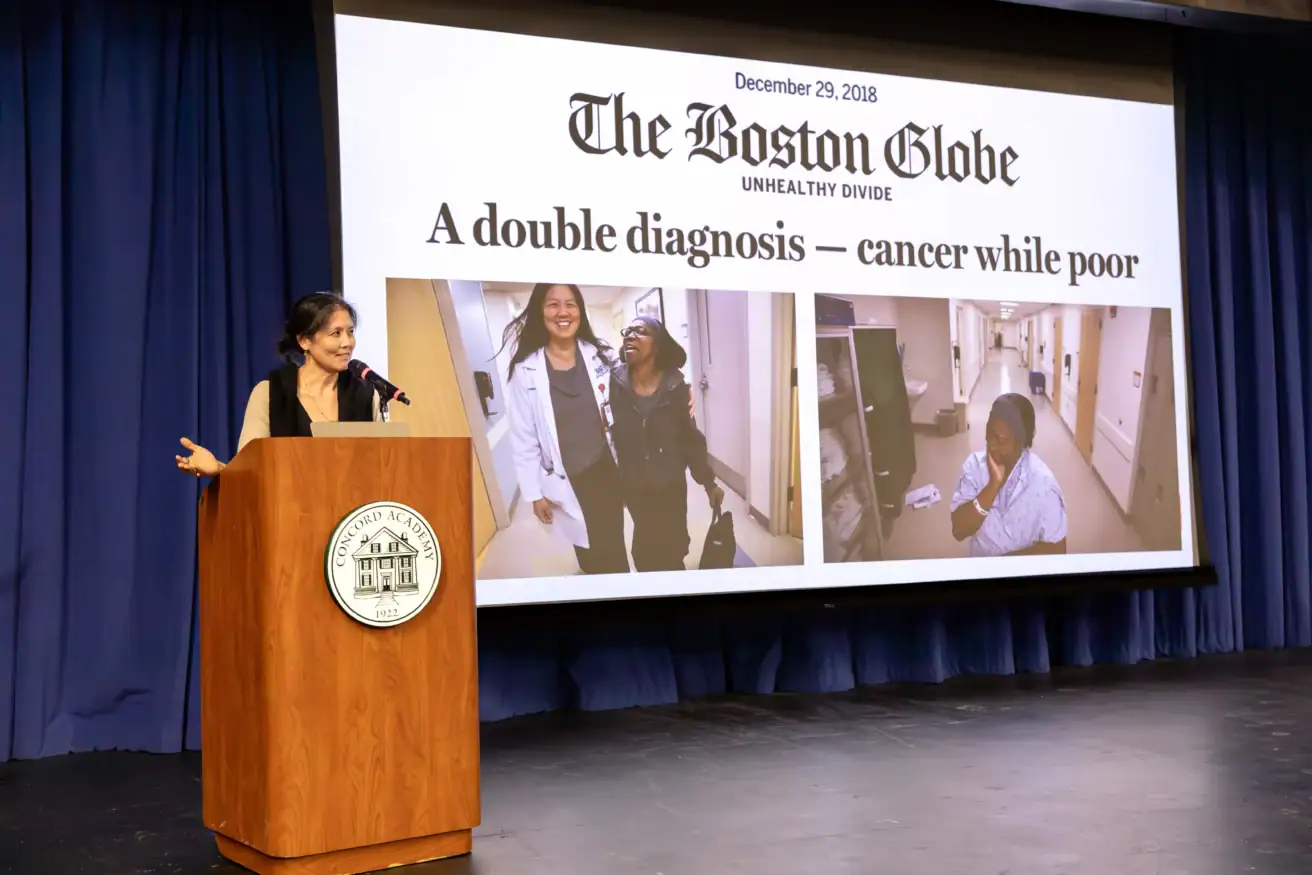

“We privilege the privileged,” Ko said. “If you have wealth, you will get great care, and the denial to get care based on poverty, lack of insurance, and racism is the legacy and reality of our current health system.” She showed a graph from the New England Journal of Medicine, charting the survival gap between Black and white women over time. Black women, she explained, have a 40% higher risk of dying of breast cancer.

The factors of these disparities are complex and interrelated, and they commonly contribute to a pattern of patient denial, Ko explained. For women living in poverty, financial instability, language barriers, and the significant challenges of taking time off work or family care to receive medical attention can lead to delayed diagnosis and treatment. Even once patients start getting care, being treated for cancer can become a “watershed moment” leading to financial collapse, she said, sharing the story of one of her patients who could not work during chemotherapy and, no longer able to pay rent, lost her housing. For insured patients whose income barely disqualifies them for assistance programs, high co-pays can also be ruinous.

Ko detailed the systems that health care teams at hospitals such as Boston Medical Center have developed to mitigate these inequities: BMC contains a food pantry and provides robust interpreter, health care navigation, and social work services. “These types of services get really strong because they have to,” she said.

Although well-intentioned individuals keep trying to fill such gaps, she acknowledged, “it’s a much bigger problem to fix than these one-offs,” requiring the development of more equitable systems. In the meantime, she suggested, how we talk about patients’ experiences matters.

Through her clinical practice, Ko understands how difficult it can be for underserved patients to keep appointments and follow medication schedules. While patients can often be labeled “difficult” or “noncompliant” in their medical records, “I see something different,” Ko said. “I see a patient who lacks trust.” She said medical care providers have the responsibility to earn that trust, give their underserved patients extra time, help them schedule appointments and scans, and affirm their lived experiences.

Ko explained that many academic studies of health care disparities are hindered by the quality of available data and subject to selection bias; their authors don’t have a practical understanding of the intersection of societal conditions and treatment outcomes because they don’t practice in hospitals that serve these patients. “The granular experience of navigating the medical system for the underserved is not adequately captured in the literature,” she said.

Shedding light on this disconnection is Ko’s current project as she completes a fellowship year at the Harvard Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study. At Radcliffe, she’s working on a book, Seeing the Unseen, to bring public attention to health care inequities through the stories of some of her patients, humanizing the experiences of women diagnosed with breast cancer for whom she has provided care.

Speaking at Concord Academy, Ko tied the power of personal stories to her own experience—as a child of Chinese immigrants, as a CA student for whom belonging had sometimes been a struggle, and now as a medical professional motivated to help shape a more just health care system. “I always felt that this CA tradition of the chapel was an antidote to that feeling of not having a place to belong,” she said. “Because here at CA, I think our community’s opportunity to connect with each person’s authentic self every few days as a ritual in a chapel helped me see people as individuals with multitudes.”