Muchos Méxicos

Inspired by a student, a new interdisciplinary bilingual class at CA is collaborative in every respect

Story by Heidi Koelz

Trip photos by Ana Topoleanu

On a chilly spring afternoon at Concord Academy, students in Carmen Welton and Jeffrey Richey’s Muchos Méxicos course discussed recent events in a warmer clime. They considered the roots of current conflicts, using terms such as los derechos (rights) and la rabia (rage). They learned why March 8, International Women’s Day, is an occasion not for celebration but for collective grief and activism in Latin America, where demonstrations against gender-based violence have rolled through manycities in recent years. They discussed sociological concepts around inequality—la misoginia internalizada, el dolor generacional (internalized misogyny, intergenerational trauma).

In twos and threes, the students examined photographs of graffiti on a concrete barrier in Mexico City, taken during a CA trip just weeks earlier. They jotted notes on their desks in dry-erase marker as they discussed the spray-painted slogans. Then Welton, a Spanish teacher, charted their inferences on a whiteboard.

“Los reclamos,” she said. “Grievances. How do you define that word in English?”

Students called out responses: complaints, issues with something.

“Something specific,” Welton clarified. “To me, it implies an expectation from an institution.”

“Or a society, or a culture,” Richey, a history teacher, added.

“Perhaps something you have the right to expect will be fixed,” Welton said.

The teachers’ easy classroom exchange resulted from intensive cooperation over the previous year. Welton and Richey created Muchos Méxicos with Department X funding from the Faculty Leadership Endowed Fund, an initiative of the Centennial Campaign for Concord Academy. Department X fosters professional development through cross-disciplinary exchange, supporting new curricula and experiential learning.

“To know at every stage that you’re encouraged and supported and have complete intellectual freedom” to work on the course is meaningful, says Richey, who also advises Alianza, CA’s Latinx affinity group.

He and Welton planned the cross-listed Spanish and history course in fall 2023. They created a framework that will allow either of them to offer the course in the future, and they made the most of the one-time chance to pilot it together this spring.

Throughout the semester, they traded off instruction fluidly—sometimes reinforcing one another, sometimes countering from a different perspective, always thinking together on the spot along with students. They established conceptual frameworks, then asked students to wonder about them and to interrogate artifacts and texts, including songs, news stories, and scholarly articles. While many readings were in English, students posted on discussion boards in Spanish, the language they spoke in class more than 80% of the time. They switched to English only if they struggled to express an abstraction, an option that let them communicate more complex ideas than they’d be able to in a typical language class.

Anni Taylor ’24, whose parents are Argentine and Puerto Rican, found expressing herself in “Spanglish” comforting; she says her comprehension is stronger than her spoken Spanish. “I just felt like I was talking at home,” she says. “Nobody’s going to judge me. Being able to speak Spanish to practice it but not be pressured to dumb down ideas to make them understandable was refreshing.”

In a typical advanced language class, Anni says, sometimes students “have really good ideas they don’t always know how to bring forward.” In Muchos Méxicos, by contrast, the focus was less on getting the language right than on holding meaningful discussion.

Using Spanish words for cultural ideas that don’t have exact English equivalents was a benefit, Anni says. For example, students learned about the muxe, a group the Zapotec people of modern-day Oaxaca, Mexico, historically considered a third gender.

As the course’s title suggests, students began to see many Mexicos as they explored the stories of often-marginalized people foregrounded by three guiding themes: Indigeneities, inequalities, and revolutions. “It was like an amalgamation of a bunch of different subjects and classes, which made it so much more engaging,” Anni says.

Just as important to her was seeing Welton and Richey navigate different approaches to topics and classroom policies. She says she learned from their willingness to disagree and to show they didn’t have everything figured out.

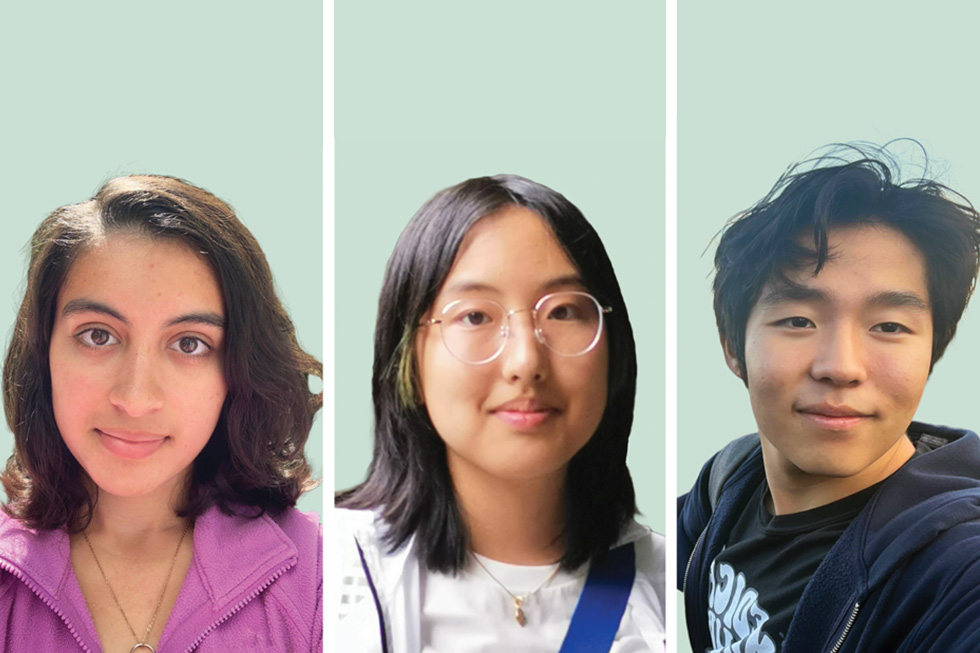

Other students shared similar sentiments. “They could be in the middle of teaching something and you could tell they were learning from each other,” says Yehjin Hwang ’24. “It was amazing to watch how deliberate they were with every step.”

Yehjin was enthusiastic about this experimental melding of disciplines. Richey introduced more lectures and class discussions than are typical of a Spanish class, she says, and compared with most history classes, “the things we talked about were a lot more personally meaningful.”

To her surprise, the oral assessment (el artefacto) after the first unit was one of her favorite activities. From a list of 10 terms, the teachers asked students to explain two concepts they had discussed in the course and how they related to each other. “It ended up being a very cool way to explore,” Yehjin says. “I let my thoughts wander, and I ended up talking about my heritage and drew parallels between maiz as a staple food in Mexico and Korean kimchi.”

Later, students gave slide presentations. While oral assignments are common in language classes, Richey says the format is gaining momentum in other disciplines at CA. The artefactos allowed students to take on the role of teachers while the teachers assessed their linguistic and analytical syntheses.

The class is also notable because the idea originated with a student. When Anghelo Chavira Barrera ’24 enrolled as a 9th grader at Concord Academy, he was impressed by the range of history electives but disappointed that none focused on his home country, Mexico. Born in the United States but raised in Mexico City, he wanted CA students to better understand his culture. After hearing peers express stereotypical assumptions about Mexican immigrants, Anghelo says he wanted to “leave a legacy” at CA by helping his peers investigate Mexican identity.

He initially proposed a conference; it didn’t work out. But in his junior year, Richey’s first at CA and Welton’s first as head of the Modern and Classical Languages Department, Anghelo approached Welton with his idea for a class taught in Spanish on the history of Mexico. She recognized a need that dovetailed with her experiences with other students, and she connected with Richey.

Using Anghelo’s idea as a springboard, they envisioned linking autobiography to academic study, and they saw that by reflecting on their disciplines’ priorities and teaching practices, they could cover new pedagogical ground and ultimately share their experience with their CA colleagues.

After the school approved their Department X application, Richey and Welton met weekly. Anghela was frequently included as well. The three share Mexican heritage, and they often held their planning sessions in Spanish.

“It was the first time I saw people really excited about this idea,” Anghelo says. “CA faculty-student connections are amazing, and we really bonded over heritage and language. We had common trust without even knowing each other.”

In fall 2023, Anghelo completed a departmental study with Richey, researching the history of Mexican emigration from the 1980s through the 2000s. For his senior project, which both Richey and Welton advised, Anghelo interviewed Latin American immigrants to the U.S. to gather their stories of perseverance in the face of adversity.

Though he hadn’t previously taken a Spanish course at CA (a native speaker, he instead studied Mandarin), he enrolled in Muchos Méxicos this spring, wanting to see it come to fruition. And though he was familiar with Mexican history, the class gave him a chance to reconsider from a scholarly perspective the cultural narratives he had learned in childhood.

Take the controversial figure of La Malinche, a 16th-century Nahua woman who aided the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, interpreting for, advising, and becoming a consort to the conquistador Hernán Cortés. “Growing up, I heard her bashed as a traitor, someone who betrayed her people for her own interests,” Anghelo says. “But this course pushed me to reconsider her story from a less biased standpoint, to see the whole context—what were her conditions, what were her options.”

Anghelo takes pride in having modeled what’s possible for an ardent CA student interested in collaborating with faculty. “I want people to remember that a student started this,” he says, and he hopes the course continues.

“We were grateful to Anghelo for recognizing this need for both the content and the interdisciplinary approach,” Welton says.

Over spring break in March, Welton and Richey led a CA trip to Mexico for 10 Spanish-language students. Many of them belonged to Alianza, and two were enrolled in Mucho Méxicos. They started in Mexico City’s historic center, where they observed evidence of Tenochtitlan, the former Aztec Empire capital that was built on an island in Lake Texcoco. Mexico’s capital now occupies the entire lake basin. Afterward, they traveled to Bucerías, on the Pacific coast. Nearby they met and spoke with several artisans, including weavers, potters, and chocolate makers, as well as farmers and local high school students.

“We wanted students to encounter the human side of Mexico, to access the lived experience and vibrant culture in a different part of the country than most U.S. visitors go,” Richey says.

He and Welton worked with Human Connections, a travel organization that empowers local communities by fostering conversations with visitors that increase understanding and shift perspectives. It was important to the CA teachers that the experience was not a typical service or cultural immersion trip.

“What was so powerful about it was how we honored the fact that people all over the world have important stories to tell, and that we’re interested in and value the full breadth and depth of human experience,” Welton says.

Students embraced the encounters. “There was a lot more critical thinking and conversation than I expected, which I loved,” says Noah Garcia ’24, Alianza co-head and a student in Muchos Méxicos. The trip was one of his first outside the United States, though he had visited family in Puerto Rico.

He particularly enjoyed eating at a farm-to-table restaurant in Bucerías with a friend who shares his Latin American heritage. “We both took a bite and started crying,” he says. “The taste was so familiar.” It got him thinking about growing up in the Bronx, in New York, where diverse Latin American cultures have mixed—and how the flavor of his meal had become familiar.

Every evening before dinner, the group discussed the interactions they’d had that day. A theme that emerged was what it means to have privilege. Over and over, the people the group met expressed their sense of being privileged to do what they do. Students began asking if el privilegio has the same connotations in Spanish as in English.

Welton says she explained that the root concept is identical: feeling fortunate, enriched, vibrant, and fulfilled. “There are so many ways to have privilege,” she says. “It was powerful to get to this place of recognizing that when we talk about privilege at CA, we’re actually talking about a narrow slice of what that entails.”

For Noah, who had never considered himself privileged, the question lingered. “It made me think about how talking about privilege, in the way I usually hear, can separate us,” he says.

Kai Feingold ’24 also carried this inquiry back to the Muchos Méxicos class after the trip. “We got to listen to a lot of people’s experiences without interjecting or imposing ourselves,” Kai says. “Everyone who goes to CA should know how privileged they are, but if you think you’re privileged, as in better than others, you won’t learn anything.”

For her part, Welton recognizes “the privilege of being able to adapt to student interest and excitement” that teachers have at CA, and the special circumstance that allowed her and Richey to teach together, not simply in parallel, to create an organic professional development experience.

“Interdisciplinarity was one of our top goals,” Richey says. “Sometimes we had radically different attitudes toward a specific thing, and students noticed that’s allowed.” The class worked, Richey says, because he and Welton “hold each other in high regard, and we both felt pressure not to let each other down.”

Welton adds that, by exploring and reconciling their pedagogical differences, “we practiced trust every day.” And both found themselves changing.

Welton says the experiment with a bilingual classroom “lessened my sense of distrust of using English in strategic ways.”

“We were constantly negotiating that fluidity between languages based on where we could extract the most meaning,” she says. “There’s a valuable skill, in and of itself, that students are gaining.” It’s also an experience truer to the way people who speak multiple languages communicate.

Richey says he felt empowered, even recognizing times he reached his own “language ceiling”—he began to use Spanish more often in his other history courses. “I’m less afraid now to admit my limitations,” he says. “I wanted students to see that modeled as well.”

Working interdisciplinarily, he says, “requires a sacrifice of ego and vulnerability.” He wouldn’t have it any other way: “I’ve learned what CA is through this partnership.”